A 14-year-old Minnesota girl is fighting criminal charges that have the potential to destroy her future, including her ability to obtain housing, to enroll in college programs, and even to pursue some career paths. Her case does not involve harm to others. It does not involve damage to property. And it does not have anything to do with illegal substances.

Rather her young life could be ruined all because she sent an explicit Snapchat of herself to a boy she liked.

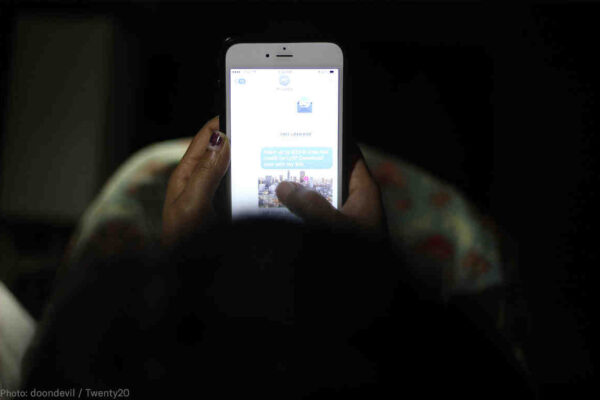

In the case, Jane Doe used the phone-based application Snapchat to send a revealing selfie to a boy at her school in Southern Minnesota. He went on to make a copy and distribute it to other students without Jane’s permission. Even though Jane didn’t victimize anybody, Rice County’s prosecutor charged her with felony distribution of child pornography. A conviction, or even a guilty plea to a lesser charge, would require Jane to spend 10 years on the sex offender registry.

Sending sexually suggestive text messages and explicit photos or videos of oneself has become so commonplace that it has a name — sexting. Conservative estimates on the prevalence of adolescent sexting are that 12 percent of adolescents aged 12-17 have sent an explicit image of themselves to another person at some point in their life. A 2012 survey by the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center (MARC) of 18-year-olds found 30 percent had sent nude pictures during high school, and 45 percent had received them.

We can all agree that sexual abuse of children is abhorrent and that our criminal laws should punish that abuse. And an important means of combatting sexual abuse of children is to prosecute those who create, possess, and disseminate works that are a permanent record of that abuse.

In Minnesota, two statutes criminalize the creation, possession, and dissemination of child pornography. The policy and purpose behind Minnesota’s law is “to protect minors from the physical and psychological damage caused by their being used in pornographic work depicting sexual conduct which involves minors” and “to protect the identity of minors who are victimized by involvement in the pornographic work, and to protect minors from future involvement in pornographic work depicting sexual conduct.”

The purpose of the law — protecting children — matters when it comes to laws that impose criminal penalties for speech. For instance, laws that criminalize adult pornography violate the First Amendment.

But in New York v. Ferber, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that distributing child pornography is interconnected with the sexual abuse of children because the material is a permanent record of the abuse and its distribution perpetuates a market for the production of material that requires the sexual exploitation of children. Because the purpose of criminalizing child pornography is to protect the “physiological, emotional, and mental health of the child” victim, they are not the same as bans on adult pornography. Therefore, child pornography bans are allowable under the First Amendment.

But what about when there is no victim? In 2002, in a case called Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, the Supreme Court struck down a law prohibiting “virtual” child pornography produced without victimizing actual children because the law did not have the same child protection justification found in Ferber.

Jane created the sext of her own body. She was not an exploited child victim. She was exhibiting normal adolescent behavior in the digital age.

Learning to think of oneself as a sexual being and dealing with sexual feelings is an important part of adolescence, and sexual experimentation is one aspect of the “trying on” of different personalities and new behaviors that is necessary to the process of identity development, according to Dr. Jennifer Woolard, an associate professor of psychology at Georgetown University. Or as Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists Dr. Lynn E. Ponton and Dr. Samuel Judice put it, “[T]hrough experimentation and risk-taking ... adolescents develop their identity and discover who they will be.”

And even if Jane could be considered an exploited child victim, punishing her will not “protect” her. It will only cause her more harm. Harm that will follow her throughout her adult life.

It is nonsensical to suggest that Jane is both a victim and the perpetrator of her own abuse. Her attorney has asked the court to dismiss the charges, and the ACLU of Minnesota has filed an amicus brief in support of that motion. We asked the court to recognize the constitutional problems with punishing Jane and pointed to the growing national consensus around the idea that adolescent sexting should not be addressed through oppressive criminal prosecutions.